Inventing Demand (On Purpose or By Accident)

Reflecting on the recent Valentine’s Day holiday, my attention was actually more drawn to the day that precedes it. February 13th was once a meaningless day, but thanks to an episode of the amazing television show Parks & Recreation, it has transformed into the very meaningful Galentine’s Day.

Galentine’s Day is a celebration of female friendship, or as Leslie Knope explains it, “ladies celebrating ladies.” In this writer’s opinion, that is certainly a noble cause. What’s interesting, though, is that this unofficial holiday didn’t exist before the P&R episode, also titled “Galentine’s Day,” which aired on February 11th, 2010. Since then, and in particular, over the last five years, the prevalence of Galentine’s Day has only grown.

Just like it’s historic neighbor, Galentine’s Day involves spending money on food, drinks, gifts, and more drinks. In other words, instead of augmenting behavior, this episode actually invented a totally new behavior. And because of that, money is being spent.

As you’d expect, when a serendipitously good thing happens, companies are there monitize it. The holiday had a jump in popularity in 2016, so in 2017 brands like Sprinkles Cupcakes, Lyft, Shari’s Berries, and Target began taking part in the festivities, offering deals and discounts accordingly. In fact, Target went so far as to roll out a line of Galentine’s Day-themed products.

For comparison’s sake, Americans spent an estimated $20.7 billion on Valentine’s Day in 2019. If Galentine’s Day increases holiday spending by 2%, that’s an additional $414 million in purchases. That’s really serious money.

I’m not overly-critical of these corporate behaviors, every other holiday is already a cash grab anyway. What I’m pointing out is that by inventing a buyer behavior, this television episode also invented a market that didn’t exist before. Like I said at the top, 99% of media & advertising exist to augment buyer behavior, but in some rare cases, it actually invents new behaviors and births markets.

This brought up another question: has this happened before?

Spoilers: it has!

And guess what. The best example from history is also about celebrating relationships. However, this time it happened completely by design.

Cut to 1888. De Beers Consolidated Mines, Ltd. (now just De Beers) is formed immediately following the discovery of massive diamond mines in South Africa. They create an unbelievable monopoly on the mining, distributing, and selling of diamonds. But, by the 1930s, the Great Depression and the saturation of diamonds on the market drive both the price and demand down. That’s never a good sign.

So, instead of bracing for the end, they developed an advertising strategy. They would use product placement in film (televisions in homes weren’t a thing yet) to show off gaudy diamond rings as a symbol of everlasting love. Then, they’d have fashion icons discuss the importance of diamonds in a relationship on the radio nationwide.

Then, as diamond demand was driven up through these efforts, they expanded their strategy. They rolled out a program across the 125 leading newspapers in the world dedicated to a discussion of the diamonds Hollywood celebrities were wearing each week.

Finally, they unveiled the A Diamond Is Forever advertising campaign and cemented the idea that an engagement wasn’t legitimate without a diamond engagement ring. It was a symbol of how loved the woman was and how successful the man was. And it worked.

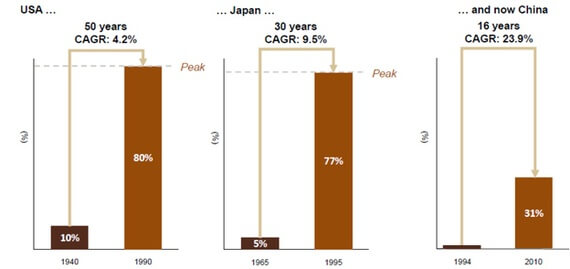

In fact, in 1940, only 10% of Americans proposed with a diamond engagement ring. By 1990, that number rose to 80%. Put another way, between 1939 and 1979, De Beers’ wholesale diamond sales in the US grew from $23 million to $2.1 billion, and their advertising budget rose 4900%. That’s not a typo.

Because it happened on purpose over a long period of time, what De Beers did seems infinitely more sinister. And it may be. But, at the end of the day, it’s accomplishing a very similar thing. By inventing a buyer behavior, proposing with a diamond engagement ring that costs two months’ salary (also a De Beers-invented concept), they made billions of dollars.

While Galentine’s Day doesn’t benefit the creators of Parks & Rec or NBC, who aired it, someone is definitely getting paid. Americans are spending money by the millions for a good, wholesome cause – all because an episode of a beloved television show made it seem like the right thing to do.